Opal Costello

31/03/2022

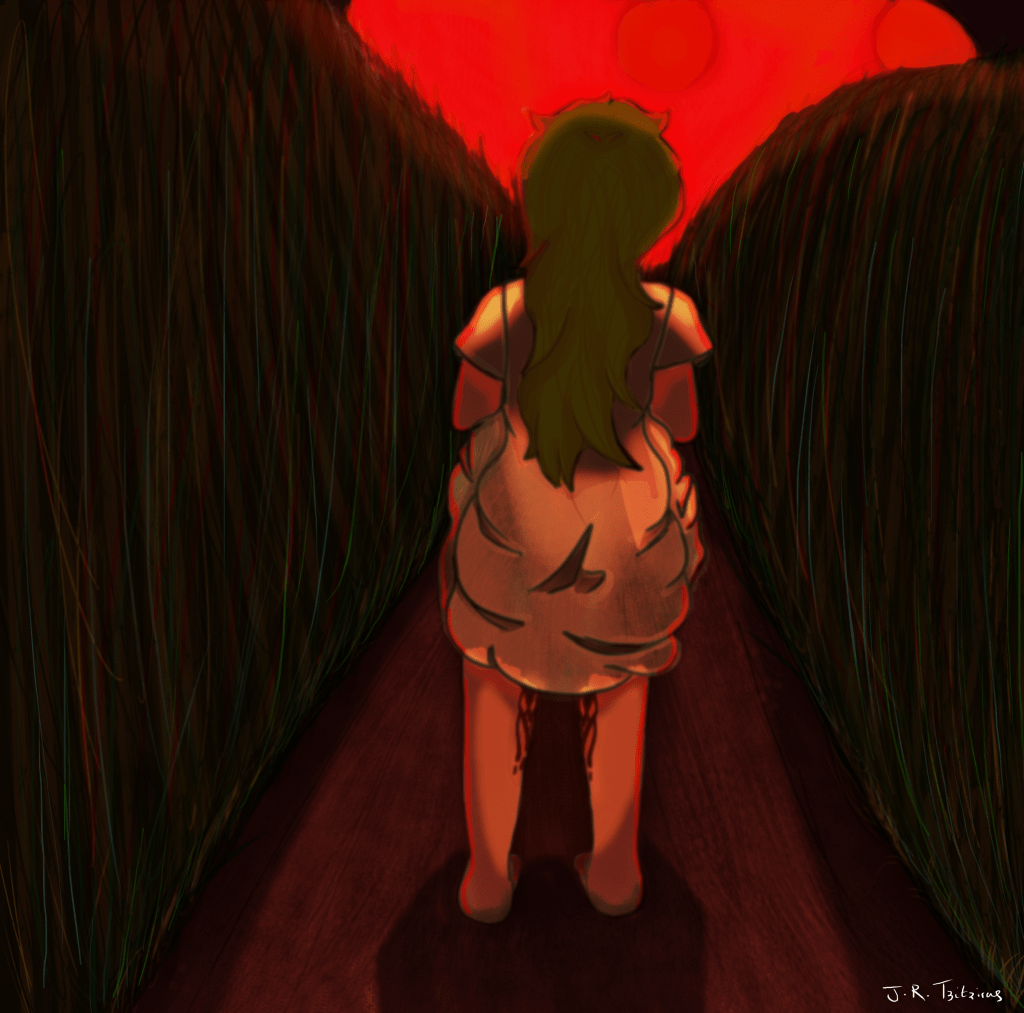

Image description: a young woman with blonde hair stands in a dark field. She is surrounded by green and lit in a red glow. She wears a light-coloured dress bunched up in her hands and has blood running down her legs.

Once the house is still, I creep past the dreams of my parents. I’m careful not to interrupt them as I’ve come to understand the luxury of dreams. In the morning they’ll wake with cemented lungs and insincere words congesting their throat, and so I tiptoe, allowing them their rest. I crawl out the roughhewn window and into the night. Stagnant and unforgiving air greets my already flushed cheeks as summer continues to lord over us even in mid-March. I run. I do so swiftly, almost madly. My limbs begin to ache, and my tongue stiffens, unable to adjust to the acrid taste of iron filling my mouth. I travel along the veins of this sleepy yet brutal town of mine. I know the houses that litter these streets intimately, I have eaten amongst their tables and shared moments with their owners. My eyes linger on silhouettes illuminated by candlelight. I wonder how many of my neighbours are awake, praying for an unfamiliar name to be called.

Above the canopy of endless barren trees, the moon is mine. She watches as my secret trickles down my leg, as finally I’m bare. Breadcrumbs of my fertility scatter along my feet, visible only for a moment before sinking into the hungry earth. It’s a hideous burden, having to hide it. The pity is tiring too, the carefulness of the women swollen with babe. It’s better than being a lamb, I think behind a kind smile.

Men are different. They don’t bother softening their eyes in my direction. I’m purely ornamental to them, like a Yule ball – shiny and hollow – unable to host their seed or grow their harvest, and therefore insignificant.

I still for a moment, amongst the browning and diseased foliage. Soon, this will change. Life will return. How strange it is. The thirst for green. When the colour of life is red.

I arrive home just before dawn, breathless. My parents haven’t stirred yet, so this will be my only time to bathe freely. My garments are heavy from a combination of my fluids, unable to help myself I bring them to my nose and inhale. Scents that should tinge my cheeks pink tickle my nostrils. Sour, tangy and almost balsamic. My tongue feels heavy and wet.

I ease my body into the tub, droplets of my exhaustion merge with the near seething water. I stay until my fingers prune and the water turns the colour of rust. I watch crimson clots float to the surface like rose petals.

A gown waits for me on my bed, brown and limp. The colour of old blood. Stealing mother’s cloth is too risky, so I fashion my own from tissue. It’s uncomfortable and full feeling, but a stain could be ruinous. The creak of a well-worn mattress alerts me to my parent’s stirring. Mother approaches my door quietly, as if I’m a deer one twig snap away from disappearing into the woods. My parents and I chew our meagre breakfast to the tune of roaring stomachs, our eyes never meet, and we don’t speak. We don’t speak about the empty chair that sits beside me, or how it has been empty for a year now.

I walk alongside my parents to the fields. My stomach sinks with every step, until I’m kicking it along the pavement. The peace I felt last night is gone, absorbed by the light. They feel it too, the heaviness. I hear it in their uniform footsteps beside me. I can’t help but reminisce about the last time, about her. We must all look like ghosts, she’d said, spinning in a bone white gown. I was in awe of her fearlessness, until her number was called, and the façade fell. Eating sickened me. Every bite was her, a seed a tooth, a grape an eye. A week later, as I mourned my sister, I felt it: the dull ache below my stomach, followed by the stream of red.

We funnel into the small field, the dry grass softening our footfalls. I’m unable to distinguish anyone amongst the sea of colourless hand-me-downs, but it doesn’t stop me from looking. For them. The potential. The Mayor takes his position at the centre of the stage. His large belly protrudes over his tight slacks. I imagine a faceless girl in a white gown trapped inside of it, trying to claw her way out.

‘Welcome, welcome! Today is an incredibly special harvest.’ The Mayor’s voice booms through the oval.

Cheers erupt, desperate and strange, like a hyena’s laugh. Hungry and carnivorous. I take my place amongst the fellow brown cloaks. All of them are older than my mother. I look out of place. A kitten amongst cats.

‘I know, I know. You’ve all felt it…the thinning. Our last harvest served us well, but it is time for another.’

I am lopsided and hot.

‘Ladies, please. Come forth!’

They line up behind him, meek as newborn kittens. I recognise them all. I’ve shared so much with them: lunches, books and laughter. Each white-knuckled hand finds another. Nausea bubbles up my throat.

‘Twenty-five years ago, we had nothing; we starved! Our children were nothing but skin and bones! And so, we made a great sacrifice. We gave our most fruitful, our most precious to the earth, and we were rewarded.’

I burp. It’s foul tasting, acidic.

‘One of you beautiful girls will give us so much. You will feed us as you have been fed. And we thank you. All of you.’

A large ceramic bowl filled with small notes is carried onto the stage. There are more notes than last year, better chances. The Mayor’s fat hand dives into the bowl. His sausage fingers feel around for the right ticket. Finally, he pulls it out. I don’t breathe or blink. I just watch his blurred lips call out the number. ‘Seventeen. Lucky number seventeen!’ Eloise McLaughlin. She’s my age, give or take a few months. The crowd becomes one body of celebration. Eloise is forced forward by her peers. Their eyes aren’t soft, their hands no longer gentle. The Mayor presses his lips to her wet cheek, oblivious to the salt.

Her body, no longer her own, is shoved into the arms of her neighbours. Rehearsed thanks are said. Eventually, her eyes connect with mine, and there’s no pity or indifference. Amongst the horror, she understands my lie and cowardice.

‘Thank you for your sacrifice,’ my words fall to her feet. She’s taller than me, and I feel like a child.

Briefly, I worry her final words will expose my secret. Instead, she enfolds me within her gaunt limbs. There’s feralness to the embrace, and a softness. It’s a contradiction, in between a cradle and a choke.

‘Eat well.’ She whispers into the shell of my ear.

I will remember toothless smiles and scraped knees, as her body rots. I will remember loving her with a childlike delicacy that morphed into a brutal competition. And I will hate myself deeply and unashamedly.

Opal Costello is an emerging writer from Naarm country (Melbourne), the traditional lands of the Kulin nation. She is currently studying at Federation University and enjoys writing feminist gothic fiction. She lives with her husband and toothless cat, Elvis.